Was first published in Accountingtoday.com

Tax laws tend to be boring, so sometimes it is easier to understand something if you know the reasoning behind it.

Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, U.S. companies and resident individuals could own foreign corporations that engaged in active trade or business activities, and pay significantly lower tax rates, as long as the income was not brought back to the U.S. It’s important to understand what active business is: It’s any business where 95 percent or more of gross receipts are derived from business activities such as consulting, product sales, etc.

Passive activity is defined as investment income, or rental income where the activity is not managed by the U.S. person. There is also a limit on an active business owning passive assets. Those cannot be a majority; otherwise the business would be considered passive as well.

Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, if a business were classified as an active trade or business, the corporate entity could be operated in a foreign tax jurisdiction with a zero or very low tax rate, and only pay the taxes that are due in that jurisdiction. For example, in Ireland, the corporate tax rate is 12.5 percent, so a company could pay the lower rate and use the tax savings to invest back into the business. As a comparison, in 2017 the highest U.S. tax rate was 35 percent for corporations and 39.6 percent for individuals, so the tax savings used to be substantial.

This was not the case with passive companies or passive foreign income, where that income was considered Subpart F income and subject to U.S. taxation, whether or not it was distributed (brought back) to the U.S. The income was taxed at the highest marginal tax rate for the individual or company.

Well, guess what? The new tax laws are now coming after the active trade or business income as well. This foreign income that was previously excluded from U.S. taxation, as long as it’s active income outside the U.S. in its own standalone entity, is now subject to Subpart F income or GILTI (global intangible low-taxed income) if you prefer. There is a minor caveat here that we should mention: The foreign corporation has to be a controlled foreign corporation, or CFC. This is a corporation that has 50 percent or more U.S. resident owners, whether they are entities and/or individuals, and the individual and/or entity has to own 10 percent or more of the foreign CFC. There is also a rule that if the company is not a CFC, but has U.S. resident corporate shareholders, it can be subject to taxes on that income.

The new Tax Cuts and Jobs Act slightly softens the blow on U.S. residents by lowering the highest marginal tax rates. For individuals, the top rate declined from 39.6 to 37 percent, but for corporations the difference is much larger, from 35 to 21 percent. At a 21 percent corporate tax rate, it might not be worth it for some corporations to conduct their business outside the U.S. If you take a popular tax jurisdiction like Ireland, the corporate tax rate differential is less than 10 percentage points, and with the increased compliance expected from U.S. residents, it might just swing business owners towards the U.S.

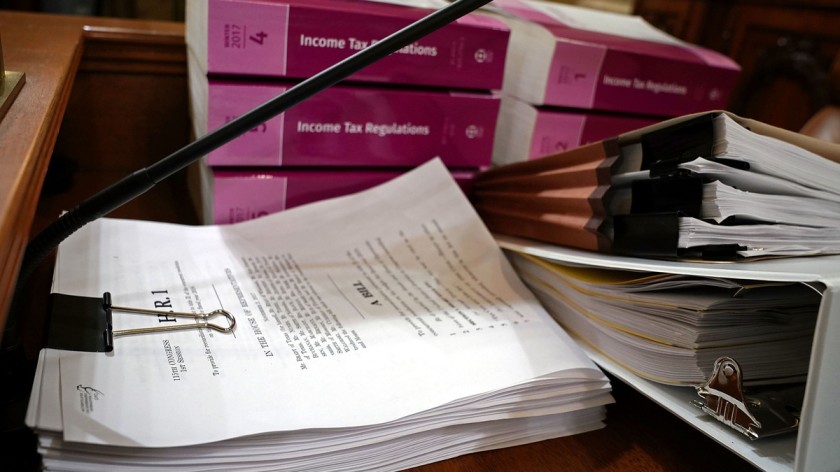

International taxation was always a complex area even before tax reform. There are plenty of tax disclosure forms that are required, and they come with a hefty $10,000 penalty per form for noncompliance.

The first thing that occurred under this international tax reform was the deemed repatriation of accumulated earnings held offshore. U.S. shareholders with 10 percent or more ownership in a CFC, and domestic corporations with more than 10 percent ownership in foreign corporations, were required to include their pro-rata share of the accumulated earnings and profits in their income.

The repatriations calculations are very complex, but in a nutshell they are a 15.5 percent tax rate on cash assets, and an 8 percent tax rate on non-cash assets. Because the impact might be financially straining on certain taxpayers, taxpayers were allowed to make an election to pay this tax over an eight-year period.

The U.S. tax system before this reform used to tax the worldwide income of its resident individuals and companies, regardless of the location where it was earned. However, the tax reform has moved the U.S. to a modified model of a territorial tax system. In a perfect territorial system, income is taxed only in the jurisdiction where it is earned. The U.S. model is a modified version because it is only available to U.S. C-type corporations who have received a 100 percent dividend exemption against distributions from foreign corporations of which they own 10 percent or more.

While we thought the new tax law would simplify the Tax Code for everyone, one portion of international tax reform brought us one of the most complex calculations, in my opinion: GILTI. I will try to explain GILTI in the most simplistic form possible. The idea here is to tax U.S. individuals and companies on all the income generated by their CFCs in countries with tax rates below 13.125 percent (while it may seem an odd number, it is essentially the reduced 10.5 percent tax rate discussed later in this paragraph, divided by the 80 percent foreign tax credit also discussed later in this paragraph). This is to discourage U.S. individuals or companies from shifting profits outside the U.S., especially on mobile assets like intellectual property, and hold them overseas for the long term. Foreign CFC affiliates of U.S. individuals or companies that have in excess of a 10 percent return on the overseas tangible capital assets, minus depreciation, will be taxed on that income generated by the tangible assets at their U.S. marginal tax rate (21 percent for corporations, and up to 37 percent for individuals). U.S. corporations, but not individuals and partnerships, can claim a 50 percent deduction on GILTI, making their effective tax rate on that income 10.5 percent (50 percent deduction on the 21 percent corporate tax rate). Corporations subject to this tax will be able to claim a foreign tax credit up to 80 percent of the taxes that were paid on GILTI.

A new alternative tax was introduced for large C-type corporations called BEAT (Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax). It applies to C-type corporations with more than $500 million in gross receipts based on a three-year average. The idea is to calculate a 10 percent tax on modified alternative income of the U.S. corporation, where this modified calculation adds back deductions taken for certain payments made to foreign affiliates.

Tax reform also increased the disclosure and reporting requirements, which were somewhat gruesome, to begin with. It is extremely challenging to navigate this new environment, as the laws are new, and there are no precedents and court cases to follow this early on. The only guidance is in the new tax laws, and interpretations of those might slightly vary among different tax professionals due to their complexity.

There are still plenty of planning opportunities for taxpayers affected by international tax reform. So as we say in many of our tax return footnote disclosures, “Please consult your tax professional.” Or in this case, “Please consult your international tax professional.”